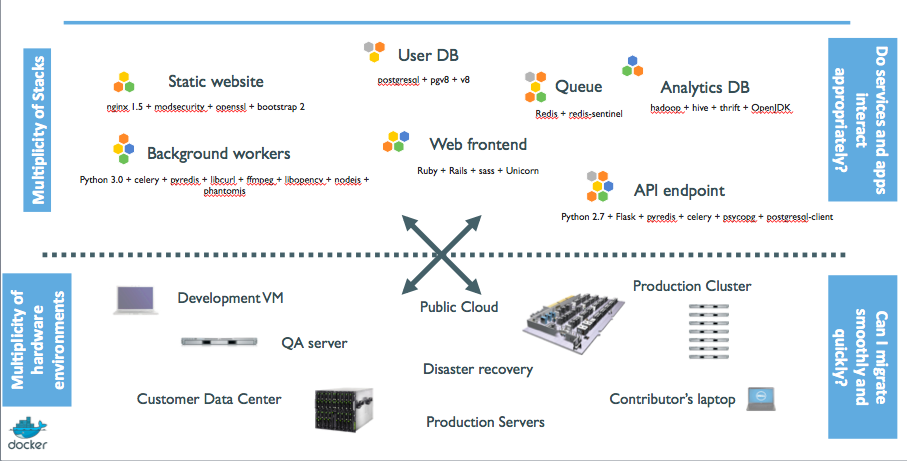

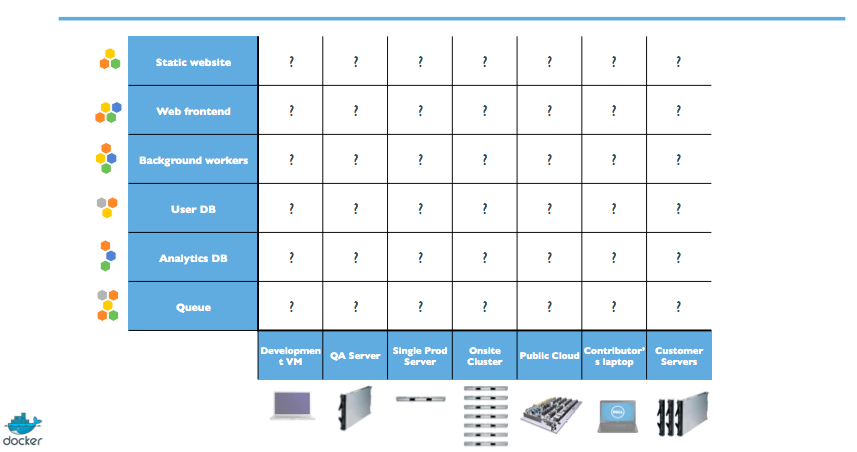

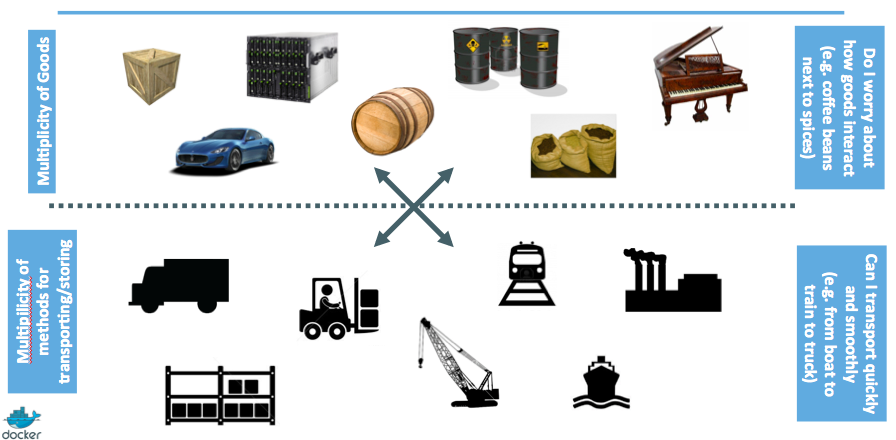

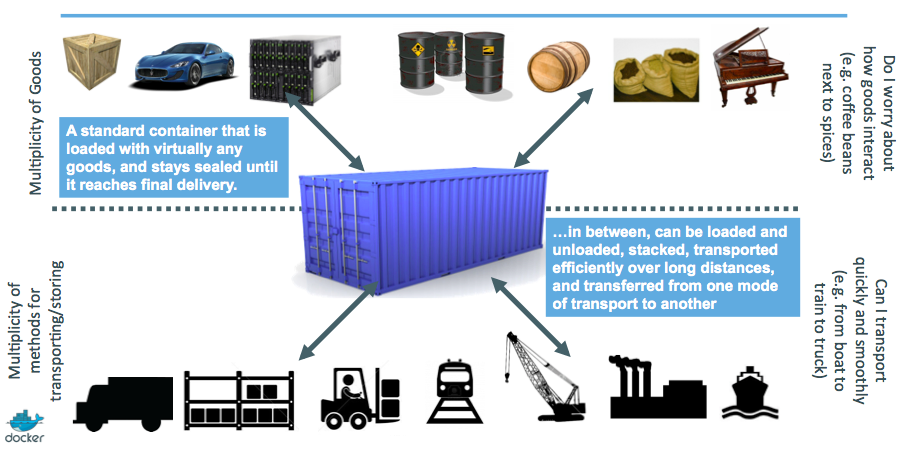

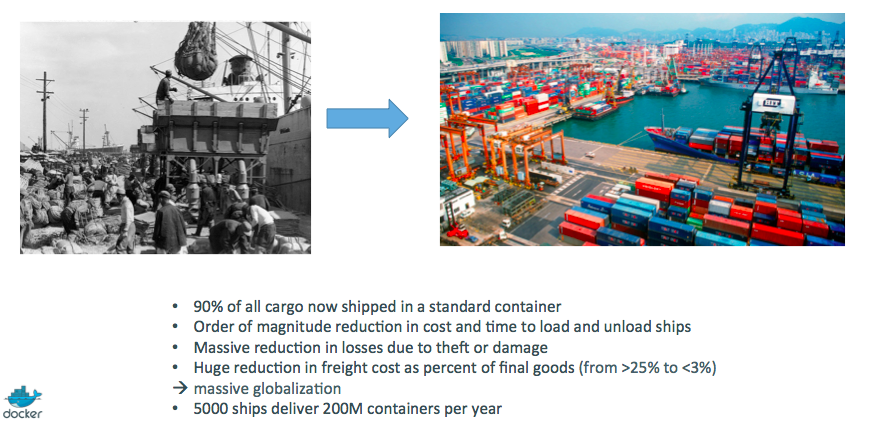

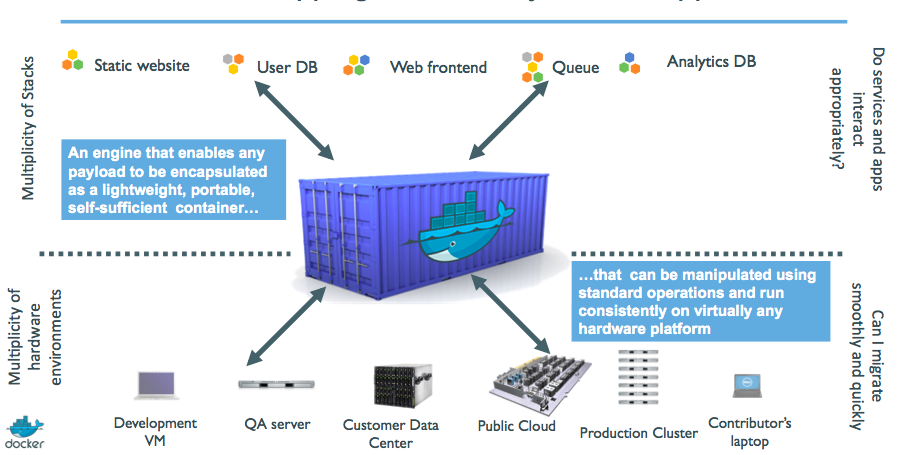

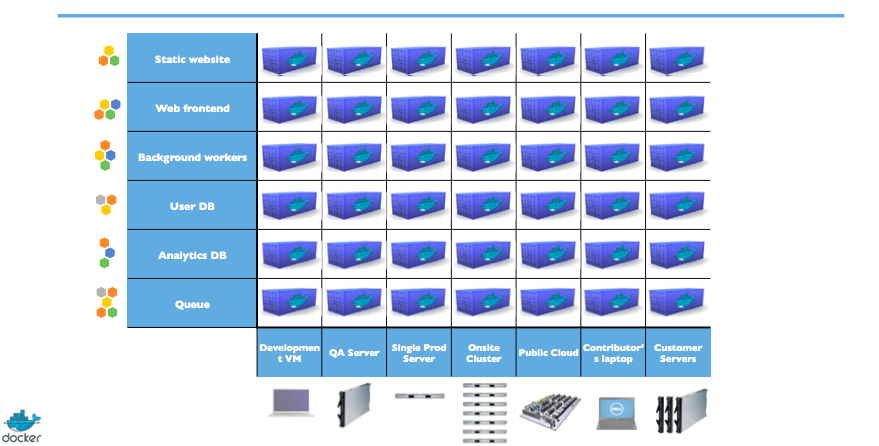

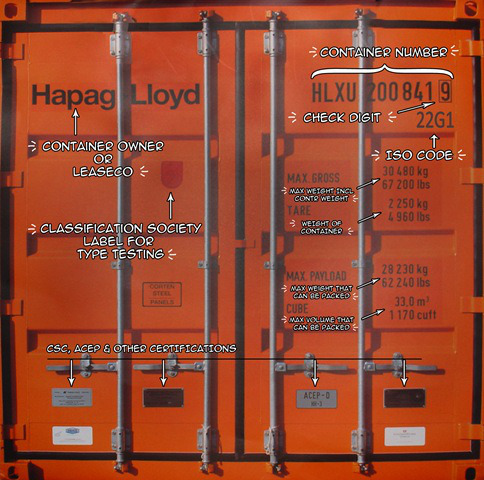

class: title, self-paced Introduction to containers in an airgapped environment<br/> <!-- .nav[*Self-paced version*] --> .debug[ ``` ``` These slides have been built from commit: 00d7d7f [shared/title.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/title.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-introductions class: title Introductions .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-1) | [Next part](#toc-docker-ft-overview) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Introductions - Let's do a quick intro. - I am: - 👨🏽🦲 Marco Verleun, container adept. - Who are you and what do you want to learn? <!-- ⚠️ This slide should be customized by the tutorial instructor(s). --> <!-- - Hello! We are: - 👷🏻♀️ AJ ([@s0ulshake], [EphemeraSearch], [Quantgene]) - 🚁 Alexandre ([@alexbuisine], Enix SAS) - 🐳 Jérôme ([@jpetazzo], Ardan Labs) - 🐳 Jérôme ([@jpetazzo], Enix SAS) - 🐳 Jérôme ([@jpetazzo], Tiny Shell Script LLC) --> <!-- - The training will run for 4 hours, with a 10 minutes break every hour (the middle break will be a bit longer) --> <!-- - The workshop will run from XXX to YYY - There will be a lunch break at ZZZ (And coffee breaks!) --> <!-- - Feel free to interrupt for questions at any time - *Especially when you see full screen container pictures!* - Live feedback, questions, help: --> <!-- - You ~~should~~ must ask questions! Lots of questions! (especially when you see full screen container pictures) - Use to ask questions, get help, etc. --> <!-- [@alexbuisine]: <https://twitter.com/alexbuisine> [EphemeraSearch]: <https://ephemerasearch.com/> [@jpetazzo]: <https://twitter.com/jpetazzo> [@s0ulshake]: <https://twitter.com/s0ulshake> [Quantgene]: <https://www.quantgene.com/> --> .debug[[logistics-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/logistics-v2.md)] --- ## Exercises - There is a series of exercises - To make the most out of the training, please try the exercises! (it will help to practice and memorize the content of the day) - There are git repo's that you have to clone to download content. More on this later. .debug[[logistics-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/logistics-v2.md)] --- class: in-person ## Where are we going to run our containers? .debug[[shared/connecting-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/connecting-v2.md)] --- class: in-person, pic  .debug[[shared/connecting-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/connecting-v2.md)] --- class: in-person ## You get a cluster of cloud VMs - Each person gets a private cluster of cloud VMs (not shared with anybody else) - They'll remain up for the duration of the workshop - You should have a (virtual) little card with login+password+IP addresses - You can automatically SSH from one VM to another - The nodes have aliases: `node1`, `node2`, etc. .debug[[shared/connecting-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/connecting-v2.md)] --- class: in-person ## Connecting to our lab environment ### `webssh` - Open http://A.B.C.D:1080 in your browser and you should see a login screen - Enter the username and password and click `connect` - You are now logged in to `node1` of your cluster - Refresh the page if the session times out .debug[[shared/connecting-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/connecting-v2.md)] --- class: in-person ## Connecting to our lab environment from the CLI .lab[ - Log into the first VM (`node1`) with your SSH client: ```bash ssh `user`@`A.B.C.D` ``` (Replace `user` and `A.B.C.D` with the user and IP address provided to you) <!-- ```bash for N in $(awk '/\Wnode/{print $2}' /etc/hosts); do ssh -o StrictHostKeyChecking=no $N true done ``` ```bash ### FIXME find a way to reset the cluster, maybe? ``` --> ] You should see a prompt looking like this: ```bash [A.B.C.D] (...) user@node1 ~ $ ``` If anything goes wrong — ask for help! .debug[[shared/connecting-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/connecting-v2.md)] --- class: in-person ## `tailhist` - The shell history of the instructor is available online in real time - Note the IP address of the instructor's virtual machine (A.B.C.D) - Open http://A.B.C.D:1088 in your browser and you should see the history - The history is updated in real time (using a WebSocket connection) - It should be green when the WebSocket is connected (if it turns red, reloading the page should fix it) .debug[[shared/connecting-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/connecting-v2.md)] --- ## Doing or re-doing the workshop on your own? - Use something like [Play-With-Docker](http://play-with-docker.com/) or [Play-With-Kubernetes](https://training.play-with-kubernetes.com/) Zero setup effort; but environment are short-lived and might have limited resources - Create your own cluster (local or cloud VMs) Small setup effort; small cost; flexible environments - Create a bunch of clusters for you and your friends ([instructions](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/master/prepare-vms)) Bigger setup effort; ideal for group training <!-- ## For a consistent Kubernetes experience ... - If you are using your own Kubernetes cluster, you can use [jpetazzo/shpod](https://github.com/jpetazzo/shpod) - `shpod` provides a shell running in a pod on your own cluster - It comes with many tools pre-installed (helm, stern...) - These tools are used in many demos and exercises in these slides - `shpod` also gives you completion and a fancy prompt - It can also be used as an SSH server if needed --> .debug[[shared/connecting-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/connecting-v2.md)] --- class: self-paced ## Get your own Docker nodes - If you already have some Docker nodes: great! - If not: let's get some thanks to Play-With-Docker .lab[ - Go to http://www.play-with-docker.com/ - Log in - Create your first node <!-- ```open http://www.play-with-docker.com/``` --> ] You will need a Docker ID to use Play-With-Docker. (Creating a Docker ID is free.) .debug[[shared/connecting-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/connecting-v2.md)] --- ## We will (mostly) interact with node1 only *These remarks apply only when using multiple nodes, of course.* - Unless instructed, **all commands must be run from the first VM, `node1`** - We will only check out/copy the code on `node1` - During normal operations, we do not need access to the other nodes - If we had to troubleshoot issues, we would use a combination of: - SSH (to access system logs, daemon status...) - Docker API (to check running containers and container engine status) <!-- ## Terminals Once in a while, the instructions will say: <br/>"Open a new terminal." There are multiple ways to do this: - create a new window or tab on your machine, and SSH into the VM; - use screen or tmux on the VM and open a new window from there. You are welcome to use the method that you feel the most comfortable with. --> <!-- ## Tmux cheat sheet [Tmux](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tmux) is a terminal multiplexer like `screen`. *You don't have to use it or even know about it to follow along. <br/> But some of us like to use it to switch between terminals. <br/> It has been preinstalled on your workshop nodes.* - Ctrl-b c → creates a new window - Ctrl-b n → go to next window - Ctrl-b p → go to previous window - Ctrl-b " → split window top/bottom - Ctrl-b % → split window left/right - Ctrl-b Alt-1 → rearrange windows in columns - Ctrl-b Alt-2 → rearrange windows in rows - Ctrl-b arrows → navigate to other windows - Ctrl-b , → rename window - Ctrl-b d → detach session - tmux attach → re-attach to session --> .debug[[shared/connecting-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/connecting-v2.md)] --- ## A brief introduction - This was initially written to support in-person, instructor-led workshops and tutorials - These materials are maintained by [Jérôme Petazzoni](https://twitter.com/jpetazzo) and [multiple contributors](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/graphs/contributors) - You can also follow along on your own, at your own pace - We included as much information as possible in these slides - We recommend having a mentor to help you ... - ... Or be comfortable spending some time reading the Docker [documentation](https://docs.docker.com/) ... - ... And looking for answers in the [Docker forums](https://forums.docker.com), [StackOverflow](http://stackoverflow.com/questions/tagged/docker), and other outlets .debug[[containers/intro.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/intro.md)] --- class: self-paced ## Hands on, you shall practice - Nobody ever became a Jedi by spending their lives reading Wookiepedia - Likewise, it will take more than merely *reading* these slides to make you an expert - These slides include *tons* of demos, exercises, and examples - They assume that you have access to a machine running Docker - If you are attending a workshop or tutorial: <br/>you will be given specific instructions to access a cloud VM - If you are doing this on your own: <br/>we will tell you how to install Docker or access a Docker environment .debug[[containers/intro.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/intro.md)] --- ## Accessing these slides now - We recommend that you open these slides in your browser: https://training.verleun.org/ - Use arrows to move to next/previous slide (up, down, left, right, page up, page down) - Type a slide number + ENTER to go to that slide - The slide number is also visible in the URL bar (e.g. .../#123 for slide 123) .debug[[shared/about-slides-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/about-slides-v2.md)] --- ## These slides are open source - You are welcome to use, re-use, share these slides - These slides are written in Markdown - The sources of many slides are available in a public GitHub repository: https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training .debug[[shared/about-slides-v2.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/about-slides-v2.md)] --- name: toc-part-1 ## Part 1 - [Introductions](#toc-introductions) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-part-2 ## Part 2 - [Docker 30,000ft overview](#toc-docker-ft-overview) - [Our first containers](#toc-our-first-containers) - [Background containers](#toc-background-containers) - [Restarting and attaching to containers](#toc-restarting-and-attaching-to-containers) - [Naming and inspecting containers](#toc-naming-and-inspecting-containers) - [Getting inside a container](#toc-getting-inside-a-container) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-part-3 ## Part 3 - [Understanding Docker images](#toc-understanding-docker-images) - [Airgapped images](#toc-airgapped-images) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-part-4 ## Part 4 - [Building images interactively](#toc-building-images-interactively) - [Building Docker images with a Dockerfile](#toc-building-docker-images-with-a-dockerfile) - [`CMD` and `ENTRYPOINT`](#toc-cmd-and-entrypoint) - [Exercise — writing Dockerfiles](#toc-exercise--writing-dockerfiles) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-part-5 ## Part 5 - [Container networking basics](#toc-container-networking-basics) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-part-6 ## Part 6 - [Application Configuration](#toc-application-configuration) - [Logging](#toc-logging) - [Container Super-structure](#toc-container-super-structure) - [Links and resources](#toc-links-and-resources) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] .debug[[shared/toc.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/toc.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-docker-ft-overview class: title Docker 30,000ft overview .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-introductions) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-our-first-containers) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Docker 30,000ft overview In this lesson, we will learn about: * Why containers (non-technical elevator pitch) * Why containers (technical elevator pitch) * How Docker helps us to build, ship, and run * The history of containers We won't actually run Docker or containers in this chapter (yet!). Don't worry, we will get to that fast enough! .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- ## Elevator pitch ### (for your manager, your boss...) .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- ## OK... Why the buzz around containers? * The software industry has changed * Before: * monolithic applications * long development cycles * single environment * slowly scaling up * Now: * decoupled services * fast, iterative improvements * multiple environments * quickly scaling out .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- ## Deployment becomes very complex * Many different stacks: * languages * frameworks * databases * Many different targets: * individual development environments * pre-production, QA, staging... * production: on prem, cloud, hybrid .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: pic ## The deployment problem  .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: pic ## The matrix from hell  .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: pic ## The parallel with the shipping industry  .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: pic ## Intermodal shipping containers  .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: pic ## A new shipping ecosystem  .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: pic ## A shipping container system for applications  .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: pic ## Eliminate the matrix from hell  .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- ## Results * [Dev-to-prod reduced from 9 months to 15 minutes (ING)]( https://www.docker.com/sites/default/files/CS_ING_01.25.2015_1.pdf) * [Continuous integration job time reduced by more than 60% (BBC)]( https://www.docker.com/sites/default/files/CS_BBCNews_01.25.2015_1.pdf) * [Deploy 100 times a day instead of once a week (GILT)]( https://www.docker.com/sites/default/files/CS_Gilt%20Groupe_03.18.2015_0.pdf) * [70% infrastructure consolidation (MetLife)]( https://www.docker.com/customers/metlife-transforms-customer-experience-legacy-and-microservices-mashup) * [60% infrastructure consolidation (Intesa Sanpaolo)]( https://blog.docker.com/2017/11/intesa-sanpaolo-builds-resilient-foundation-banking-docker-enterprise-edition/) * [14x application density; 60% of legacy datacenter migrated in 4 months (GE Appliances)]( https://www.docker.com/customers/ge-uses-docker-enable-self-service-their-developers) * etc. .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- ## Elevator pitch ### (for your fellow devs and ops) .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- ## Escape dependency hell 1. Write installation instructions into an `INSTALL.txt` file 2. Using this file, write an `install.sh` script that works *for you* 3. Turn this file into a `Dockerfile`, test it on your machine 4. If the Dockerfile builds on your machine, it will build *anywhere* 5. Rejoice as you escape dependency hell and "works on my machine" Never again "worked in dev - ops problem now!" .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- ## On-board developers and contributors rapidly 1. Write Dockerfiles for your application components 2. Use pre-made images from the Docker Hub (mysql, redis...) 3. Describe your stack with a Compose file 4. On-board somebody with two commands: ```bash git clone ... docker-compose up ``` With this, you can create development, integration, QA environments in minutes! .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Implement reliable CI easily 1. Build test environment with a Dockerfile or Compose file 2. For each test run, stage up a new container or stack 3. Each run is now in a clean environment 4. No pollution from previous tests Way faster and cheaper than creating VMs each time! .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Use container images as build artefacts 1. Build your app from Dockerfiles 2. Store the resulting images in a registry 3. Keep them forever (or as long as necessary) 4. Test those images in QA, CI, integration... 5. Run the same images in production 6. Something goes wrong? Rollback to previous image 7. Investigating old regression? Old image has your back! Images contain all the libraries, dependencies, etc. needed to run the app. .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Decouple "plumbing" from application logic 1. Write your code to connect to named services ("db", "api"...) 2. Use Compose to start your stack 3. Docker will setup per-container DNS resolver for those names 4. You can now scale, add load balancers, replication ... without changing your code Note: this is not covered in this intro level workshop! .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## What did Docker bring to the table? ### Docker before/after .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Formats and APIs, before Docker * No standardized exchange format. <br/>(No, a rootfs tarball is *not* a format!) * Containers are hard to use for developers. <br/>(Where's the equivalent of `docker run debian`?) * As a result, they are *hidden* from the end users. * No re-usable components, APIs, tools. <br/>(At best: VM abstractions, e.g. libvirt.) Analogy: * Shipping containers are not just steel boxes. * They are steel boxes that are a standard size, with the same hooks and holes. .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Formats and APIs, after Docker * Standardize the container format, because containers were not portable. * Make containers easy to use for developers. * Emphasis on re-usable components, APIs, ecosystem of standard tools. * Improvement over ad-hoc, in-house, specific tools. .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Shipping, before Docker * Ship packages: deb, rpm, gem, jar, homebrew... * Dependency hell. * "Works on my machine." * Base deployment often done from scratch (debootstrap...) and unreliable. .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Shipping, after Docker * Ship container images with all their dependencies. * Images are bigger, but they are broken down into layers. * Only ship layers that have changed. * Save disk, network, memory usage. .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Example Layers: * CentOS * JRE * Tomcat * Dependencies * Application JAR * Configuration .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Devs vs Ops, before Docker * Drop a tarball (or a commit hash) with instructions. * Dev environment very different from production. * Ops don't always have a dev environment themselves ... * ... and when they do, it can differ from the devs'. * Ops have to sort out differences and make it work ... * ... or bounce it back to devs. * Shipping code causes frictions and delays. .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Devs vs Ops, after Docker * Drop a container image or a Compose file. * Ops can always run that container image. * Ops can always run that Compose file. * Ops still have to adapt to prod environment, but at least they have a reference point. * Ops have tools allowing to use the same image in dev and prod. * Devs can be empowered to make releases themselves more easily. .debug[[containers/Docker_Overview.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Docker_Overview.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-our-first-containers class: title Our first containers .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-docker-ft-overview) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-background-containers) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- class: title # Our first containers  .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Objectives At the end of this lesson, you will have: * Seen Docker in action. * Started your first containers. .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Hello World In your Docker environment, just run the following command: ```bash $ docker run busybox echo hello world hello world ``` (If your Docker install is brand new, you will also see a few extra lines, corresponding to the download of the `busybox` image.) .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## That was our first container! * We used one of the smallest, simplest images available: `busybox`. * `busybox` is typically used in embedded systems (phones, routers...) * We ran a single process and echo'ed `hello world`. .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## A more useful container Let's run a more exciting container: ```bash $ docker run -it ubuntu root@04c0bb0a6c07:/# ``` * This is a brand new container. * It runs a bare-bones, no-frills `ubuntu` system. * `-it` is shorthand for `-i -t`. * `-i` tells Docker to connect us to the container's stdin. * `-t` tells Docker that we want a pseudo-terminal. .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Do something in our container Try to run `figlet` in our container. ```bash root@04c0bb0a6c07:/# figlet hello bash: figlet: command not found ``` Alright, we need to install it. .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Install a package in our container We want `figlet`, so let's install it: ```bash root@04c0bb0a6c07:/# apt-get update ... Fetched 1514 kB in 14s (103 kB/s) Reading package lists... Done root@04c0bb0a6c07:/# apt-get install figlet Reading package lists... Done ... ``` One minute later, `figlet` is installed! .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Try to run our freshly installed program The `figlet` program takes a message as parameter. ```bash root@04c0bb0a6c07:/# figlet hello _ _ _ | |__ ___| | | ___ | '_ \ / _ \ | |/ _ \ | | | | __/ | | (_) | |_| |_|\___|_|_|\___/ ``` Beautiful! 😍 .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- class: in-person ## Counting packages in the container Let's check how many packages are installed there. ```bash root@04c0bb0a6c07:/# dpkg -l | wc -l 97 ``` * `dpkg -l` lists the packages installed in our container * `wc -l` counts them How many packages do we have on our host? .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- class: in-person ## Counting packages on the host Exit the container by logging out of the shell, like you would usually do. (E.g. with `^D` or `exit`) ```bash root@04c0bb0a6c07:/# exit ``` Now, try to: * run `dpkg -l | wc -l`. How many packages are installed? * run `figlet`. Does that work? .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- class: self-paced ## Comparing the container and the host Exit the container by logging out of the shell, with `^D` or `exit`. Now try to run `figlet`. Does that work? (It shouldn't; except if, by coincidence, you are running on a machine where figlet was installed before.) .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Host and containers are independent things * We ran an `ubuntu` container on an Linux/Windows/macOS host. * They have different, independent packages. * Installing something on the host doesn't expose it to the container. * And vice-versa. * Even if both the host and the container have the same Linux distro! * We can run *any container* on *any host*. (One exception: Windows containers can only run on Windows hosts; at least for now.) .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Where's our container? * Our container is now in a *stopped* state. * It still exists on disk, but all compute resources have been freed up. * We will see later how to get back to that container. .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Starting another container What if we start a new container, and try to run `figlet` again? ```bash $ docker run -it ubuntu root@b13c164401fb:/# figlet bash: figlet: command not found ``` * We started a *brand new container*. * The basic Ubuntu image was used, and `figlet` is not here. .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Where's my container? * Can we reuse that container that we took time to customize? *We can, but that's not the default workflow with Docker.* * What's the default workflow, then? *Always start with a fresh container.* <br/> *If we need something installed in our container, build a custom image.* * That seems complicated! *We'll see that it's actually pretty easy!* * And what's the point? *This puts a strong emphasis on automation and repeatability. Let's see why ...* .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Pets vs. Cattle * In the "pets vs. cattle" metaphor, there are two kinds of servers. * Pets: * have distinctive names and unique configurations * when they have an outage, we do everything we can to fix them * Cattle: * have generic names (e.g. with numbers) and generic configuration * configuration is enforced by configuration management, golden images ... * when they have an outage, we can replace them immediately with a new server * What's the connection with Docker and containers? .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Local development environments * When we use local VMs (with e.g. VirtualBox or VMware), our workflow looks like this: * create VM from base template (Ubuntu, CentOS...) * install packages, set up environment * work on project * when done, shut down VM * next time we need to work on project, restart VM as we left it * if we need to tweak the environment, we do it live * Over time, the VM configuration evolves, diverges. * We don't have a clean, reliable, deterministic way to provision that environment. .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- ## Local development with Docker * With Docker, the workflow looks like this: * create container image with our dev environment * run container with that image * work on project * when done, shut down container * next time we need to work on project, start a new container * if we need to tweak the environment, we create a new image * We have a clear definition of our environment, and can share it reliably with others. * Let's see in the next chapters how to bake a custom image with `figlet`! ??? :EN:- Running our first container :FR:- Lancer nos premiers conteneurs .debug[[containers/First_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/First_Containers.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-background-containers class: title Background containers .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-our-first-containers) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-restarting-and-attaching-to-containers) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- class: title # Background containers  .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## Objectives Our first containers were *interactive*. We will now see how to: * Run a non-interactive container. * Run a container in the background. * List running containers. * Check the logs of a container. * Stop a container. * List stopped containers. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## A non-interactive container We will run a small custom container. This container just displays the time every second. ```bash $ docker run jpetazzo/clock Fri Feb 20 00:28:53 UTC 2015 Fri Feb 20 00:28:54 UTC 2015 Fri Feb 20 00:28:55 UTC 2015 ... ``` * This container will run forever. * To stop it, press `^C`. * Docker has automatically downloaded the image `jpetazzo/clock`. * This image is a user image, created by `jpetazzo`. * We will hear more about user images (and other types of images) later. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## When `^C` doesn't work... Sometimes, `^C` won't be enough. Why? And how can we stop the container in that case? .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## What happens when we hit `^C` `SIGINT` gets sent to the container, which means: - `SIGINT` gets sent to PID 1 (default case) - `SIGINT` gets sent to *foreground processes* when running with `-ti` But there is a special case for PID 1: it ignores all signals! - except `SIGKILL` and `SIGSTOP` - except signals handled explicitly TL,DR: there are many circumstances when `^C` won't stop the container. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Why is PID 1 special? - PID 1 has some extra responsibilities: - it starts (directly or indirectly) every other process - when a process exits, its processes are "reparented" under PID 1 - When PID 1 exits, everything stops: - on a "regular" machine, it causes a kernel panic - in a container, it kills all the processes - We don't want PID 1 to stop accidentally - That's why it has these extra protections .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## How to stop these containers, then? - Start another terminal and forget about them (for now!) - We'll shortly learn about `docker kill` .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## Run a container in the background Containers can be started in the background, with the `-d` flag (daemon mode): ```bash $ docker run -d jpetazzo/clock 47d677dcfba4277c6cc68fcaa51f932b544cab1a187c853b7d0caf4e8debe5ad ``` * We don't see the output of the container. * But don't worry: Docker collects that output and logs it! * Docker gives us the ID of the container. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## List running containers How can we check that our container is still running? With `docker ps`, just like the UNIX `ps` command, lists running processes. ```bash $ docker ps CONTAINER ID IMAGE ... CREATED STATUS ... 47d677dcfba4 jpetazzo/clock ... 2 minutes ago Up 2 minutes ... ``` Docker tells us: * The (truncated) ID of our container. * The image used to start the container. * That our container has been running (`Up`) for a couple of minutes. * Other information (COMMAND, PORTS, NAMES) that we will explain later. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## Starting more containers Let's start two more containers. ```bash $ docker run -d jpetazzo/clock 57ad9bdfc06bb4407c47220cf59ce21585dce9a1298d7a67488359aeaea8ae2a ``` ```bash $ docker run -d jpetazzo/clock 068cc994ffd0190bbe025ba74e4c0771a5d8f14734af772ddee8dc1aaf20567d ``` Check that `docker ps` correctly reports all 3 containers. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## Viewing only the last container started When many containers are already running, it can be useful to see only the last container that was started. This can be achieved with the `-l` ("Last") flag: ```bash $ docker ps -l CONTAINER ID IMAGE ... CREATED STATUS ... 068cc994ffd0 jpetazzo/clock ... 2 minutes ago Up 2 minutes ... ``` .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## View only the IDs of the containers Many Docker commands will work on container IDs: `docker stop`, `docker rm`... If we want to list only the IDs of our containers (without the other columns or the header line), we can use the `-q` ("Quiet", "Quick") flag: ```bash $ docker ps -q 068cc994ffd0 57ad9bdfc06b 47d677dcfba4 ``` .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## Combining flags We can combine `-l` and `-q` to see only the ID of the last container started: ```bash $ docker ps -lq 068cc994ffd0 ``` At a first glance, it looks like this would be particularly useful in scripts. However, if we want to start a container and get its ID in a reliable way, it is better to use `docker run -d`, which we will cover in a bit. (Using `docker ps -lq` is prone to race conditions: what happens if someone else, or another program or script, starts another container just before we run `docker ps -lq`?) .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## View the logs of a container We told you that Docker was logging the container output. Let's see that now. ```bash $ docker logs 068 Fri Feb 20 00:39:52 UTC 2015 Fri Feb 20 00:39:53 UTC 2015 ... ``` * We specified a *prefix* of the full container ID. * You can, of course, specify the full ID. * The `logs` command will output the *entire* logs of the container. <br/>(Sometimes, that will be too much. Let's see how to address that.) .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## View only the tail of the logs To avoid being spammed with eleventy pages of output, we can use the `--tail` option: ```bash $ docker logs --tail 3 068 Fri Feb 20 00:55:35 UTC 2015 Fri Feb 20 00:55:36 UTC 2015 Fri Feb 20 00:55:37 UTC 2015 ``` * The parameter is the number of lines that we want to see. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## Follow the logs in real time Just like with the standard UNIX command `tail -f`, we can follow the logs of our container: ```bash $ docker logs --tail 1 --follow 068 Fri Feb 20 00:57:12 UTC 2015 Fri Feb 20 00:57:13 UTC 2015 ^C ``` * This will display the last line in the log file. * Then, it will continue to display the logs in real time. * Use `^C` to exit. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## Stop our container There are two ways we can terminate our detached container. * Killing it using the `docker kill` command. * Stopping it using the `docker stop` command. The first one stops the container immediately, by using the `KILL` signal. The second one is more graceful. It sends a `TERM` signal, and after 10 seconds, if the container has not stopped, it sends `KILL.` Reminder: the `KILL` signal cannot be intercepted, and will forcibly terminate the container. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## Stopping our containers Let's stop one of those containers: ```bash $ docker stop 47d6 47d6 ``` This will take 10 seconds: * Docker sends the TERM signal; * the container doesn't react to this signal (it's a simple Shell script with no special signal handling); * 10 seconds later, since the container is still running, Docker sends the KILL signal; * this terminates the container. .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## Killing the remaining containers Let's be less patient with the two other containers: ```bash $ docker kill 068 57ad 068 57ad ``` The `stop` and `kill` commands can take multiple container IDs. Those containers will be terminated immediately (without the 10-second delay). Let's check that our containers don't show up anymore: ```bash $ docker ps ``` .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- ## List stopped containers We can also see stopped containers, with the `-a` (`--all`) option. ```bash $ docker ps -a CONTAINER ID IMAGE ... CREATED STATUS 068cc994ffd0 jpetazzo/clock ... 21 min. ago Exited (137) 3 min. ago 57ad9bdfc06b jpetazzo/clock ... 21 min. ago Exited (137) 3 min. ago 47d677dcfba4 jpetazzo/clock ... 23 min. ago Exited (137) 3 min. ago 5c1dfd4d81f1 jpetazzo/clock ... 40 min. ago Exited (0) 40 min. ago b13c164401fb ubuntu ... 55 min. ago Exited (130) 53 min. ago ``` ??? :EN:- Foreground and background containers :FR:- Exécution interactive ou en arrière-plan .debug[[containers/Background_Containers.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Background_Containers.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-restarting-and-attaching-to-containers class: title Restarting and attaching to containers .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-background-containers) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-naming-and-inspecting-containers) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Restarting and attaching to containers We have started containers in the foreground, and in the background. In this chapter, we will see how to: * Put a container in the background. * Attach to a background container to bring it to the foreground. * Restart a stopped container. .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- ## Background and foreground The distinction between foreground and background containers is arbitrary. From Docker's point of view, all containers are the same. All containers run the same way, whether there is a client attached to them or not. It is always possible to detach from a container, and to reattach to a container. Analogy: attaching to a container is like plugging a keyboard and screen to a physical server. .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- ## Detaching from a container (Linux/macOS) * If you have started an *interactive* container (with option `-it`), you can detach from it. * The "detach" sequence is `^P^Q`. * Otherwise you can detach by killing the Docker client. (But not by hitting `^C`, as this would deliver `SIGINT` to the container.) What does `-it` stand for? * `-t` means "allocate a terminal." * `-i` means "connect stdin to the terminal." .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- ## Detaching cont. (Win PowerShell and cmd.exe) * Docker for Windows has a different detach experience due to shell features. * `^P^Q` does not work. * `^C` will detach, rather than stop the container. * Using Bash, Subsystem for Linux, etc. on Windows behaves like Linux/macOS shells. * Both PowerShell and Bash work well in Win 10; just be aware of differences. .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Specifying a custom detach sequence * You don't like `^P^Q`? No problem! * You can change the sequence with `docker run --detach-keys`. * This can also be passed as a global option to the engine. Start a container with a custom detach command: ```bash $ docker run -ti --detach-keys ctrl-x,x jpetazzo/clock ``` Detach by hitting `^X x`. (This is ctrl-x then x, not ctrl-x twice!) Check that our container is still running: ```bash $ docker ps -l ``` .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Attaching to a container You can attach to a container: ```bash $ docker attach <containerID> ``` * The container must be running. * There *can* be multiple clients attached to the same container. * If you don't specify `--detach-keys` when attaching, it defaults back to `^P^Q`. Try it on our previous container: ```bash $ docker attach $(docker ps -lq) ``` Check that `^X x` doesn't work, but `^P ^Q` does. .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- ## Detaching from non-interactive containers * **Warning:** if the container was started without `-it`... * You won't be able to detach with `^P^Q`. * If you hit `^C`, the signal will be proxied to the container. * Remember: you can always detach by killing the Docker client. .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- ## Checking container output * Use `docker attach` if you intend to send input to the container. * If you just want to see the output of a container, use `docker logs`. ```bash $ docker logs --tail 1 --follow <containerID> ``` .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- ## Restarting a container When a container has exited, it is in stopped state. It can then be restarted with the `start` command. ```bash $ docker start <yourContainerID> ``` The container will be restarted using the same options you launched it with. You can re-attach to it if you want to interact with it: ```bash $ docker attach <yourContainerID> ``` Use `docker ps -a` to identify the container ID of a previous `jpetazzo/clock` container, and try those commands. .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- ## Attaching to a REPL * REPL = Read Eval Print Loop * Shells, interpreters, TUI ... * Symptom: you `docker attach`, and see nothing * The REPL doesn't know that you just attached, and doesn't print anything * Try hitting `^L` or `Enter` .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- class: extra-details ## SIGWINCH * When you `docker attach`, the Docker Engine sends SIGWINCH signals to the container. * SIGWINCH = WINdow CHange; indicates a change in window size. * This will cause some CLI and TUI programs to redraw the screen. * But not all of them. ??? :EN:- Restarting old containers :EN:- Detaching and reattaching to container :FR:- Redémarrer des anciens conteneurs :FR:- Se détacher et rattacher à des conteneurs .debug[[containers/Start_And_Attach.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Start_And_Attach.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-naming-and-inspecting-containers class: title Naming and inspecting containers .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-restarting-and-attaching-to-containers) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-getting-inside-a-container) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- class: title # Naming and inspecting containers  .debug[[containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md)] --- ## Objectives In this lesson, we will learn about an important Docker concept: container *naming*. Naming allows us to: * Reference easily a container. * Ensure unicity of a specific container. We will also see the `inspect` command, which gives a lot of details about a container. .debug[[containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md)] --- ## Naming our containers So far, we have referenced containers with their ID. We have copy-pasted the ID, or used a shortened prefix. But each container can also be referenced by its name. If a container is named `thumbnail-worker`, I can do: ```bash $ docker logs thumbnail-worker $ docker stop thumbnail-worker etc. ``` .debug[[containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md)] --- ## Default names When we create a container, if we don't give a specific name, Docker will pick one for us. It will be the concatenation of: * A mood (furious, goofy, suspicious, boring...) * The name of a famous inventor (tesla, darwin, wozniak...) Examples: `happy_curie`, `clever_hopper`, `jovial_lovelace` ... .debug[[containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md)] --- ## Specifying a name You can set the name of the container when you create it. ```bash $ docker run --name ticktock jpetazzo/clock ``` If you specify a name that already exists, Docker will refuse to create the container. This lets us enforce unicity of a given resource. .debug[[containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md)] --- ## Renaming containers * You can rename containers with `docker rename`. * This allows you to "free up" a name without destroying the associated container. .debug[[containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md)] --- ## Inspecting a container The `docker inspect` command will output a very detailed JSON map. ```bash $ docker inspect <containerID> [{ ... (many pages of JSON here) ... ``` There are multiple ways to consume that information. .debug[[containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md)] --- ## Parsing JSON with the Shell * You *could* grep and cut or awk the output of `docker inspect`. * Please, don't. * It's painful. * If you really must parse JSON from the Shell, use JQ! (It's great.) ```bash $ docker inspect <containerID> | jq . ``` * We will see a better solution which doesn't require extra tools. .debug[[containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md)] --- ## Using `--format` You can specify a format string, which will be parsed by Go's text/template package. ```bash $ docker inspect --format '{{ json .Created }}' <containerID> "2015-02-24T07:21:11.712240394Z" ``` * The generic syntax is to wrap the expression with double curly braces. * The expression starts with a dot representing the JSON object. * Then each field or member can be accessed in dotted notation syntax. * The optional `json` keyword asks for valid JSON output. <br/>(e.g. here it adds the surrounding double-quotes.) ??? :EN:Managing container lifecycle :EN:- Naming and inspecting containers :FR:Suivre ses conteneurs à la loupe :FR:- Obtenir des informations détaillées sur un conteneur :FR:- Associer un identifiant unique à un conteneur .debug[[containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Naming_And_Inspecting.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-getting-inside-a-container class: title Getting inside a container .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-naming-and-inspecting-containers) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-2) | [Next part](#toc-understanding-docker-images) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- class: title # Getting inside a container  .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Objectives On a traditional server or VM, we sometimes need to: * log into the machine (with SSH or on the console), * analyze the disks (by removing them or rebooting with a rescue system). In this chapter, we will see how to do that with containers. .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Getting a shell Every once in a while, we want to log into a machine. In an perfect world, this shouldn't be necessary. * You need to install or update packages (and their configuration)? Use configuration management. (e.g. Ansible, Chef, Puppet, Salt...) * You need to view logs and metrics? Collect and access them through a centralized platform. In the real world, though ... we often need shell access! .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Not getting a shell Even without a perfect deployment system, we can do many operations without getting a shell. * Installing packages can (and should) be done in the container image. * Configuration can be done at the image level, or when the container starts. * Dynamic configuration can be stored in a volume (shared with another container). * Logs written to stdout are automatically collected by the Docker Engine. * Other logs can be written to a shared volume. * Process information and metrics are visible from the host. _Let's save logging, volumes ... for later, but let's have a look at process information!_ .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Viewing container processes from the host If you run Docker on Linux, container processes are visible on the host. ```bash $ ps faux | less ``` * Scroll around the output of this command. * You should see the `jpetazzo/clock` container. * A containerized process is just like any other process on the host. * We can use tools like `lsof`, `strace`, `gdb` ... To analyze them. .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- class: extra-details ## What's the difference between a container process and a host process? * Each process (containerized or not) belongs to *namespaces* and *cgroups*. * The namespaces and cgroups determine what a process can "see" and "do". * Analogy: each process (containerized or not) runs with a specific UID (user ID). * UID=0 is root, and has elevated privileges. Other UIDs are normal users. _We will give more details about namespaces and cgroups later._ .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Getting a shell in a running container * Sometimes, we need to get a shell anyway. * We _could_ run some SSH server in the container ... * But it is easier to use `docker exec`. ```bash $ docker exec -ti ticktock sh ``` * This creates a new process (running `sh`) _inside_ the container. * This can also be done "manually" with the tool `nsenter`. .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Caveats * The tool that you want to run needs to exist in the container. * Some tools (like `ip netns exec`) let you attach to _one_ namespace at a time. (This lets you e.g. setup network interfaces, even if you don't have `ifconfig` or `ip` in the container.) * Most importantly: the container needs to be running. * What if the container is stopped or crashed? .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Getting a shell in a stopped container * A stopped container is only _storage_ (like a disk drive). * We cannot SSH into a disk drive or USB stick! * We need to connect the disk to a running machine. * How does that translate into the container world? .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Analyzing a stopped container As an exercise, we are going to try to find out what's wrong with `jpetazzo/crashtest`. ```bash docker run jpetazzo/crashtest ``` The container starts, but then stops immediately, without any output. What would MacGyver™ do? First, let's check the status of that container. ```bash docker ps -l ``` .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Viewing filesystem changes * We can use `docker diff` to see files that were added / changed / removed. ```bash docker diff <container_id> ``` * The container ID was shown by `docker ps -l`. * We can also see it with `docker ps -lq`. * The output of `docker diff` shows some interesting log files! .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Accessing files * We can extract files with `docker cp`. ```bash docker cp <container_id>:/var/log/nginx/error.log . ``` * Then we can look at that log file. ```bash cat error.log ``` (The directory `/run/nginx` doesn't exist.) .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- ## Exploring a crashed container * We can restart a container with `docker start` ... * ... But it will probably crash again immediately! * We cannot specify a different program to run with `docker start` * But we can create a new image from the crashed container ```bash docker commit <container_id> debugimage ``` * Then we can run a new container from that image, with a custom entrypoint ```bash docker run -ti --entrypoint sh debugimage ``` .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Obtaining a complete dump * We can also dump the entire filesystem of a container. * This is done with `docker export`. * It generates a tar archive. ```bash docker export <container_id> | tar tv ``` This will give a detailed listing of the content of the container. ??? :EN:- Troubleshooting and getting inside a container :FR:- Inspecter un conteneur en détail, en *live* ou *post-mortem* .debug[[containers/Getting_Inside.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Getting_Inside.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-understanding-docker-images class: title Understanding Docker images .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-getting-inside-a-container) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-airgapped-images) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- class: title # Understanding Docker images  .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Objectives In this section, we will explain: * What is an image. * What is a layer. * The various image namespaces. * How to search and download images. * Image tags and when to use them. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## What is an image? * Image = files + metadata * These files form the root filesystem of our container. * The metadata can indicate a number of things, e.g.: * the author of the image * the command to execute in the container when starting it * environment variables to be set * etc. * Images are made of *layers*, conceptually stacked on top of each other. * Each layer can add, change, and remove files and/or metadata. * Images can share layers to optimize disk usage, transfer times, and memory use. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Example for a Java webapp Each of the following items will correspond to one layer: * CentOS base layer * Packages and configuration files added by our local IT * JRE * Tomcat * Our application's dependencies * Our application code and assets * Our application configuration (Note: app config is generally added by orchestration facilities.) .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- class: pic ## The read-write layer  .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Differences between containers and images * An image is a read-only filesystem. * A container is an encapsulated set of processes, running in a read-write copy of that filesystem. * To optimize container boot time, *copy-on-write* is used instead of regular copy. * `docker run` starts a container from a given image. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- class: pic ## Multiple containers sharing the same image  .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Comparison with object-oriented programming * Images are conceptually similar to *classes*. * Layers are conceptually similar to *inheritance*. * Containers are conceptually similar to *instances*. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Wait a minute... If an image is read-only, how do we change it? * We don't. * We create a new container from that image. * Then we make changes to that container. * When we are satisfied with those changes, we transform them into a new layer. * A new image is created by stacking the new layer on top of the old image. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## A chicken-and-egg problem * The only way to create an image is by "freezing" a container. * The only way to create a container is by instantiating an image. * Help! .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Creating the first images There is a special empty image called `scratch`. * It allows to *build from scratch*. The `docker import` command loads a tarball into Docker. * The imported tarball becomes a standalone image. * That new image has a single layer. Note: you will probably never have to do this yourself. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Creating other images `docker commit` * Saves all the changes made to a container into a new layer. * Creates a new image (effectively a copy of the container). `docker build` **(used 99% of the time)** * Performs a repeatable build sequence. * This is the preferred method! We will explain both methods in a moment. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Images namespaces There are three namespaces: * Official images e.g. `ubuntu`, `busybox` ... * User (and organizations) images e.g. `jpetazzo/clock` * Self-hosted images e.g. `registry.example.com:5000/my-private/image` Let's explain each of them. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Root namespace The root namespace is for official images. They are gated by Docker Inc. They are generally authored and maintained by third parties. Those images include: * Small, "swiss-army-knife" images like busybox. * Distro images to be used as bases for your builds, like ubuntu, fedora... * Ready-to-use components and services, like redis, postgresql... * Over 150 at this point! .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## User namespace The user namespace holds images for Docker Hub users and organizations. For example: ```bash jpetazzo/clock ``` The Docker Hub user is: ```bash jpetazzo ``` The image name is: ```bash clock ``` .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Self-hosted namespace This namespace holds images which are not hosted on Docker Hub, but on third party registries. They contain the hostname (or IP address), and optionally the port, of the registry server. For example: ```bash localhost:5000/wordpress ``` * `localhost:5000` is the host and port of the registry * `wordpress` is the name of the image Other examples: ```bash quay.io/coreos/etcd gcr.io/google-containers/hugo ``` .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## How do you store and manage images? Images can be stored: * On your Docker host. * In a Docker registry. You can use the Docker client to download (pull) or upload (push) images. To be more accurate: you can use the Docker client to tell a Docker Engine to push and pull images to and from a registry. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Showing current images Let's look at what images are on our host now. ```bash $ docker images REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE fedora latest ddd5c9c1d0f2 3 days ago 204.7 MB centos latest d0e7f81ca65c 3 days ago 196.6 MB ubuntu latest 07c86167cdc4 4 days ago 188 MB redis latest 4f5f397d4b7c 5 days ago 177.6 MB postgres latest afe2b5e1859b 5 days ago 264.5 MB alpine latest 70c557e50ed6 5 days ago 4.798 MB debian latest f50f9524513f 6 days ago 125.1 MB busybox latest 3240943c9ea3 2 weeks ago 1.114 MB training/namer latest 902673acc741 9 months ago 289.3 MB jpetazzo/clock latest 12068b93616f 12 months ago 2.433 MB ``` .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Searching for images We cannot list *all* images on a remote registry, but we can search for a specific keyword: ```bash $ docker search marathon NAME DESCRIPTION STARS OFFICIAL AUTOMATED mesosphere/marathon A cluster-wide init and co... 105 [OK] mesoscloud/marathon Marathon 31 [OK] mesosphere/marathon-lb Script to update haproxy b... 22 [OK] tobilg/mongodb-marathon A Docker image to start a ... 4 [OK] ``` * "Stars" indicate the popularity of the image. * "Official" images are those in the root namespace. * "Automated" images are built automatically by the Docker Hub. <br/>(This means that their build recipe is always available.) .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Downloading images There are two ways to download images. * Explicitly, with `docker pull`. * Implicitly, when executing `docker run` and the image is not found locally. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Pulling an image ```bash $ docker pull debian:jessie Pulling repository debian b164861940b8: Download complete b164861940b8: Pulling image (jessie) from debian d1881793a057: Download complete ``` * As seen previously, images are made up of layers. * Docker has downloaded all the necessary layers. * In this example, `:jessie` indicates which exact version of Debian we would like. It is a *version tag*. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Image and tags * Images can have tags. * Tags define image versions or variants. * `docker pull ubuntu` will refer to `ubuntu:latest`. * The `:latest` tag is generally updated often. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## When to (not) use tags Don't specify tags: * When doing rapid testing and prototyping. * When experimenting. * When you want the latest version. Do specify tags: * When recording a procedure into a script. * When going to production. * To ensure that the same version will be used everywhere. * To ensure repeatability later. This is similar to what we would do with `pip install`, `npm install`, etc. .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Multi-arch images - An image can support multiple architectures - More precisely, a specific *tag* in a given *repository* can have either: - a single *manifest* referencing an image for a single architecture - a *manifest list* (or *fat manifest*) referencing multiple images - In a *manifest list*, each image is identified by a combination of: - `os` (linux, windows) - `architecture` (amd64, arm, arm64...) - optional fields like `variant` (for arm and arm64), `os.version` (for windows) .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Working with multi-arch images - The Docker Engine will pull "native" images when available (images matching its own os/architecture/variant) - We can ask for a specific image platform with `--platform` - The Docker Engine can run non-native images thanks to QEMU+binfmt (automatically on Docker Desktop; with a bit of setup on Linux) .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- ## Section summary We've learned how to: * Understand images and layers. * Understand Docker image namespacing. * Search and download images. ??? :EN:Building images :EN:- Containers, images, and layers :EN:- Image addresses and tags :EN:- Finding and transferring images :FR:Construire des images :FR:- La différence entre un conteneur et une image :FR:- La notion de *layer* partagé entre images .debug[[containers/Initial_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Initial_Images.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-airgapped-images class: title Airgapped images .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-understanding-docker-images) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-3) | [Next part](#toc-building-images-interactively) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- class: title # Airgapped images  .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Airgapped - In an airgapped environment there is no direct access to public repositories. - Images have to be converted into files and vice versa in order to import them. - Imported images can be used on a single node, repeat for multiple nodes. ;-) - Imported images can also be pushed into a internal, secure, registry. .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Objectives * We will now see how to: * Pull public images * Convert them to files * Import them on a secure node * Use them local * Tag them and push them into a secure registry .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Pulling images Let's pull a public Ubuntu image. There is no real magic here. .lab[ ```bash $ docker pull ubuntu:22.04 22.04: Pulling from library/ubuntu 837dd4791cdc: Pull complete Digest: sha256:ac58ff7fe25edc58bdf0067ca99df00014dbd032e2246d30a722fa348fd799a5 Status: Downloaded newer image for ubuntu:22.04 docker.io/library/ubuntu:22.04 ``` ] * This image has only one layer, but that is not relevant. .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Let's see how to use it local .lab[ ```bash $ docker image ls REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE ubuntu 22.04 1f6ddc1b2547 2 weeks ago 77.8MB $ docker run --rm ubuntu:22.04 uptime 08:46:39 up 1:42, 0 users, load average: 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 ``` ] * The container is started using the name of the image. .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Convert the image to a file Assume we're working on a host that is not secure but it has access to public repo's. Let's pull an image and convert it to file to ship it to a secure enviroment. .lab[ ```bash $ docker pull python:latest latest: Pulling from library/python bd73737482dd: Pull complete 6710592d62aa: Pull complete 75256935197e: Extracting 54.58MB/54.58MB c1e5026c6457: Download complete f0016544b8b9: Download complete 1d58eee51ff2: Download complete 93dc7b704cd1: Download complete caefdefa531e: Download complete $ docker save python:latest > python_image.tar ``` ] .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Clean up Remove the python image to pretend that we are now working on a secure host where we need this image. .lab[ ```bash $ docker image ls REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE python latest 0a6cd0db41a4 2 weeks ago 919MB ubuntu 22.04 1f6ddc1b2547 2 weeks ago 77.8MB $ docker image rm python:latest Untagged: python:latest Untagged: python@sha256:3a619e3c96fd4c5fc5e1998fd4dcb1f1403eb90c4c6409c70d7e80b9468df7df Deleted: sha256:0a6cd0db41a4daebb332262ddd1f61a29e88169b8c93476cb885f46d400473c8 Deleted: sha256:2107499ce10dd1004c16e7c0b47e3cb86317188b5f9a1ab64ac1968c3f56fe2c ... $ docker image ls REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE ubuntu 22.04 1f6ddc1b2547 2 weeks ago 77.8MB ``` ] .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Import image on 'secure' system Let's pretend that we copied the `tar` file to this node via secure, approved methodes. Once it is there we can import it. .lab[ ```bash $ docker image ls REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE ubuntu 22.04 1f6ddc1b2547 2 weeks ago 77.8MB $ docker load < python_image.tar 974e52a24adf: Loading layer 129.3MB/129.3MB b0df24a95c80: Loading layer 29.52MB/29.52MB ... 30563becc00e: Loading layer 11.64MB/11.64MB Loaded image: python:latest $ docker image ls REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE python latest 0a6cd0db41a4 2 weeks ago 919MB ubuntu 22.04 1f6ddc1b2547 2 weeks ago 77.8MB ``` ] .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Image locally available The imported image is available on the host where it was imported. The name of the image has not changed. This operation can be repeated throughout the organisation and the images could be stored somewhere in a filesystem in `tar` format. .lab[ ```bash $ docker run --rm -it python cat /etc/debian_version 11.7 $ ls -l total 919644 -rw-r--r-- 1 docker users 941711360 Jan 6 08:51 python_image.tar ``` ] You could also do a `tar tvf python_image.tar` .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Sharing an imported image If a local registry is available it can be used to store and share imported images. The steps are simple: * Import image * Add a new name to the image including the name of the registry (tagging the image) * Push the new name to the registry. .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Self signed certificates Let's create a certificate to simulate a more secure environment. .lab[ ```bash $ mkdir certs $ openssl req \ -newkey rsa:4096 -nodes -sha256 -keyout certs/domain.key \ -addext "subjectAltName = DNS:node1" \ -x509 -days 365 -out certs/domain.crt Generating a RSA private key ... writing new private key to 'certs/domain.key' ----- ... Common Name (e.g. server FQDN or YOUR name) []:node1 Email Address []: ``` ] .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Install certificate for docker Docker expects certificates to exist at a directory in `/etc/docker/certs.d`. This directory contains a subdir named equal to the node name of the certificate. Inside is the corresponding file. .lab[ ```bash $ sudo mkdir -p /etc/docker/certs.d/node1:443 $ sudo cp certs/domain.crt /etc/docker/certs.d/node1\:443/ca.crt $ sudo systemctl restart docker ``` ] .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Start the local registry Let's start a local registry first using a one liner. .lab[ ```bash $ docker run -d --restart=always --name registry -v "$(pwd)"/certs:/certs -e REGISTRY_HTTP_ADDR=0.0.0.0:443 -e REGISTRY_HTTP_TLS_CERTIFICATE=/certs/domain.crt -e REGISTRY_HTTP_TLS_KEY=/certs/domain.key -p 443:443 registry:2 Unable to find image 'registry:2' locally 2: Pulling from library/registry 8a49fdb3b6a5: Pull complete 58116d8bf569: Pull complete 4cb4a93be51c: Pull complete cbdeff65a266: Pull complete 6b102b34ed3d: Pull complete Digest: sha256:20d084723c951e377e1a2a5b3df316173a845e300d57ccdd8ae3ab2da3439746 Status: Downloaded newer image for registry:2 0c1a3bfe39f5d3a90d42bf97ad3e95220496317b8185a865f57a7fa5aceac68d ``` ] .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- ## Tag and push python image Assign an additional(!) name to the python image and push it into the registry .lab[ ```bash $ docker tag python:latest node1:443/python:latest $ docker image ls REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE python latest 0a6cd0db41a4 2 weeks ago 919MB node1:443/python latest 0a6cd0db41a4 2 weeks ago 919MB ubuntu 22.04 1f6ddc1b2547 2 weeks ago 77.8MB registry latest 65f3b3441f04 3 weeks ago 24MB $ docker push node1:443/python Using default tag: latest The push refers to repository [node1:443/python] 30563becc00e: Pushed 71c951de0520: Pushed 0eb817dfc4e1: Pushing [==================> ] 20.54MB/56.5MB ... 974e52a24adf: Waiting latest: digest: sha256:cbaa654007e0c2f2e2869ae69f9e9924826872d405c02647f65f5a72b597e853 size: 2007 ``` ] .debug[[airgapped/Importing_Images.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/airgapped/Importing_Images.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-building-images-interactively class: title Building images interactively .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-airgapped-images) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-building-docker-images-with-a-dockerfile) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Building images interactively In this section, we will create our first container image. It will be a basic distribution image, but we will pre-install the package `figlet`. We will: * Create a container from a base image. * Install software manually in the container, and turn it into a new image. * Learn about new commands: `docker commit`, `docker tag`, and `docker diff`. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- ## The plan 1. Create a container (with `docker run`) using our base distro of choice. 2. Run a bunch of commands to install and set up our software in the container. 3. (Optionally) review changes in the container with `docker diff`. 4. Turn the container into a new image with `docker commit`. 5. (Optionally) add tags to the image with `docker tag`. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- ## Setting up our container Start an Ubuntu container: ```bash $ docker run -it ubuntu root@<yourContainerId>:#/ ``` Run the command `apt-get update` to refresh the list of packages available to install. Then run the command `apt-get install figlet` to install the program we are interested in. ```bash root@<yourContainerId>:#/ apt-get update && apt-get install figlet .... OUTPUT OF APT-GET COMMANDS .... ``` .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- ## Inspect the changes Type `exit` at the container prompt to leave the interactive session. Now let's run `docker diff` to see the difference between the base image and our container. ```bash $ docker diff <yourContainerId> C /root A /root/.bash_history C /tmp C /usr C /usr/bin A /usr/bin/figlet ... ``` .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- class: x-extra-details ## Docker tracks filesystem changes As explained before: * An image is read-only. * When we make changes, they happen in a copy of the image. * Docker can show the difference between the image, and its copy. * For performance, Docker uses copy-on-write systems. <br/>(i.e. starting a container based on a big image doesn't incur a huge copy.) .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- ## Copy-on-write security benefits * `docker diff` gives us an easy way to audit changes (à la Tripwire) * Containers can also be started in read-only mode (their root filesystem will be read-only, but they can still have read-write data volumes) .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- ## Commit our changes into a new image The `docker commit` command will create a new layer with those changes, and a new image using this new layer. ```bash $ docker commit <yourContainerId> <newImageId> ``` The output of the `docker commit` command will be the ID for your newly created image. We can use it as an argument to `docker run`. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- ## Testing our new image Let's run this image: ```bash $ docker run -it <newImageId> root@fcfb62f0bfde:/# figlet hello _ _ _ | |__ ___| | | ___ | '_ \ / _ \ | |/ _ \ | | | | __/ | | (_) | |_| |_|\___|_|_|\___/ ``` It works! 🎉 .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- ## Tagging images Referring to an image by its ID is not convenient. Let's tag it instead. We can use the `tag` command: ```bash $ docker tag <newImageId> figlet ``` But we can also specify the tag as an extra argument to `commit`: ```bash $ docker commit <containerId> figlet ``` And then run it using its tag: ```bash $ docker run -it figlet ``` .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- ## What's next? Manual process = bad. Automated process = good. In the next chapter, we will learn how to automate the build process by writing a `Dockerfile`. ??? :EN:- Building our first images interactively :FR:- Fabriquer nos premières images à la main .debug[[containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_Interactively.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-building-docker-images-with-a-dockerfile class: title Building Docker images with a Dockerfile .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-building-images-interactively) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-cmd-and-entrypoint) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- class: title # Building Docker images with a Dockerfile  .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Objectives We will build a container image automatically, with a `Dockerfile`. At the end of this lesson, you will be able to: * Write a `Dockerfile`. * Build an image from a `Dockerfile`. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## `Dockerfile` overview * A `Dockerfile` is a build recipe for a Docker image. * It contains a series of instructions telling Docker how an image is constructed. * The `docker build` command builds an image from a `Dockerfile`. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Writing our first `Dockerfile` Our Dockerfile must be in a **new, empty directory**. 1. Create a directory to hold our `Dockerfile`. ```bash $ mkdir myimage ``` 2. Create a `Dockerfile` inside this directory. ```bash $ cd myimage $ vim Dockerfile ``` Of course, you can use any other editor of your choice. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Type this into our Dockerfile... ```dockerfile FROM ubuntu RUN apt-get update RUN apt-get install figlet ``` * `FROM` indicates the base image for our build. * Each `RUN` line will be executed by Docker during the build. * Our `RUN` commands **must be non-interactive.** <br/>(No input can be provided to Docker during the build.) * In many cases, we will add the `-y` flag to `apt-get`. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Build it! Save our file, then execute: ```bash $ docker build -t figlet . ``` * `-t` indicates the tag to apply to the image. * `.` indicates the location of the *build context*. We will talk more about the build context later. To keep things simple for now: this is the directory where our Dockerfile is located. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## What happens when we build the image? It depends if we're using BuildKit or not! If there are lots of blue lines and the first line looks like this: ``` [+] Building 1.8s (4/6) ``` ... then we're using BuildKit. If the output is mostly black-and-white and the first line looks like this: ``` Sending build context to Docker daemon 2.048kB ``` ... then we're using the "classic" or "old-style" builder. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## To BuildKit or Not To BuildKit Classic builder: - copies the whole "build context" to the Docker Engine - linear (processes lines one after the other) - requires a full Docker Engine BuildKit: - only transfers parts of the "build context" when needed - will parallelize operations (when possible) - can run in non-privileged containers (e.g. on Kubernetes) .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## With the classic builder The output of `docker build` looks like this: .small[ ```bash docker build -t figlet . Sending build context to Docker daemon 2.048kB Step 1/3 : FROM ubuntu ---> f975c5035748 Step 2/3 : RUN apt-get update ---> Running in e01b294dbffd (...output of the RUN command...) Removing intermediate container e01b294dbffd ---> eb8d9b561b37 Step 3/3 : RUN apt-get install figlet ---> Running in c29230d70f9b (...output of the RUN command...) Removing intermediate container c29230d70f9b ---> 0dfd7a253f21 Successfully built 0dfd7a253f21 Successfully tagged figlet:latest ``` ] * The output of the `RUN` commands has been omitted. * Let's explain what this output means. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Sending the build context to Docker ```bash Sending build context to Docker daemon 2.048 kB ``` * The build context is the `.` directory given to `docker build`. * It is sent (as an archive) by the Docker client to the Docker daemon. * This allows to use a remote machine to build using local files. * Be careful (or patient) if that directory is big and your link is slow. * You can speed up the process with a [`.dockerignore`](https://docs.docker.com/engine/reference/builder/#dockerignore-file) file * It tells docker to ignore specific files in the directory * Only ignore files that you won't need in the build context! .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Executing each step ```bash Step 2/3 : RUN apt-get update ---> Running in e01b294dbffd (...output of the RUN command...) Removing intermediate container e01b294dbffd ---> eb8d9b561b37 ``` * A container (`e01b294dbffd`) is created from the base image. * The `RUN` command is executed in this container. * The container is committed into an image (`eb8d9b561b37`). * The build container (`e01b294dbffd`) is removed. * The output of this step will be the base image for the next one. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## With BuildKit .small[ ```bash [+] Building 7.9s (7/7) FINISHED => [internal] load build definition from Dockerfile 0.0s => => transferring dockerfile: 98B 0.0s => [internal] load .dockerignore 0.0s => => transferring context: 2B 0.0s => [internal] load metadata for docker.io/library/ubuntu:latest 1.2s => [1/3] FROM docker.io/library/ubuntu@sha256:cf31af331f38d1d7158470e095b132acd126a7180a54f263d386 3.2s => => resolve docker.io/library/ubuntu@sha256:cf31af331f38d1d7158470e095b132acd126a7180a54f263d386 0.0s => => sha256:cf31af331f38d1d7158470e095b132acd126a7180a54f263d386da88eb681d93 1.20kB / 1.20kB 0.0s => => sha256:1de4c5e2d8954bf5fa9855f8b4c9d3c3b97d1d380efe19f60f3e4107a66f5cae 943B / 943B 0.0s => => sha256:6a98cbe39225dadebcaa04e21dbe5900ad604739b07a9fa351dd10a6ebad4c1b 3.31kB / 3.31kB 0.0s => => sha256:80bc30679ac1fd798f3241208c14accd6a364cb8a6224d1127dfb1577d10554f 27.14MB / 27.14MB 2.3s => => sha256:9bf18fab4cfbf479fa9f8409ad47e2702c63241304c2cdd4c33f2a1633c5f85e 850B / 850B 0.5s => => sha256:5979309c983a2adeff352538937475cf961d49c34194fa2aab142effe19ed9c1 189B / 189B 0.4s => => extracting sha256:80bc30679ac1fd798f3241208c14accd6a364cb8a6224d1127dfb1577d10554f 0.7s => => extracting sha256:9bf18fab4cfbf479fa9f8409ad47e2702c63241304c2cdd4c33f2a1633c5f85e 0.0s => => extracting sha256:5979309c983a2adeff352538937475cf961d49c34194fa2aab142effe19ed9c1 0.0s => [2/3] RUN apt-get update 2.5s => [3/3] RUN apt-get install figlet 0.9s => exporting to image 0.1s => => exporting layers 0.1s => => writing image sha256:3b8aee7b444ab775975dfba691a72d8ac24af2756e0a024e056e3858d5a23f7c 0.0s => => naming to docker.io/library/figlet 0.0s ``` ] .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Understanding BuildKit output - BuildKit transfers the Dockerfile and the *build context* (these are the first two `[internal]` stages) - Then it executes the steps defined in the Dockerfile (`[1/3]`, `[2/3]`, `[3/3]`) - Finally, it exports the result of the build (image definition + collection of layers) .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- class: extra-details ## BuildKit plain output - When running BuildKit in e.g. a CI pipeline, its output will be different - We can see the same output format by using `--progress=plain` .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## The caching system If you run the same build again, it will be instantaneous. Why? * After each build step, Docker takes a snapshot of the resulting image. * Before executing a step, Docker checks if it has already built the same sequence. * Docker uses the exact strings defined in your Dockerfile, so: * `RUN apt-get install figlet cowsay` <br/> is different from <br/> `RUN apt-get install cowsay figlet` * `RUN apt-get update` is not re-executed when the mirrors are updated You can force a rebuild with `docker build --no-cache ...`. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Running the image The resulting image is not different from the one produced manually. ```bash $ docker run -ti figlet root@91f3c974c9a1:/# figlet hello _ _ _ | |__ ___| | | ___ | '_ \ / _ \ | |/ _ \ | | | | __/ | | (_) | |_| |_|\___|_|_|\___/ ``` Yay! 🎉 .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Using image and viewing history The `history` command lists all the layers composing an image. For each layer, it shows its creation time, size, and creation command. When an image was built with a Dockerfile, each layer corresponds to a line of the Dockerfile. ```bash $ docker history figlet IMAGE CREATED CREATED BY SIZE f9e8f1642759 About an hour ago /bin/sh -c apt-get install fi 1.627 MB 7257c37726a1 About an hour ago /bin/sh -c apt-get update 21.58 MB 07c86167cdc4 4 days ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) CMD ["/bin 0 B <missing> 4 days ago /bin/sh -c sed -i 's/^#\s*\( 1.895 kB <missing> 4 days ago /bin/sh -c echo '#!/bin/sh' 194.5 kB <missing> 4 days ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) ADD file:b 187.8 MB ``` .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Why `sh -c`? * On UNIX, to start a new program, we need two system calls: - `fork()`, to create a new child process; - `execve()`, to replace the new child process with the program to run. * Conceptually, `execve()` works like this: `execve(program, [list, of, arguments])` * When we run a command, e.g. `ls -l /tmp`, something needs to parse the command. (i.e. split the program and its arguments into a list.) * The shell is usually doing that. (It also takes care of expanding environment variables and special things like `~`.) .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Why `sh -c`? * When we do `RUN ls -l /tmp`, the Docker builder needs to parse the command. * Instead of implementing its own parser, it outsources the job to the shell. * That's why we see `sh -c ls -l /tmp` in that case. * But we can also do the parsing jobs ourselves. * This means passing `RUN` a list of arguments. * This is called the *exec syntax*. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Shell syntax vs exec syntax Dockerfile commands that execute something can have two forms: * plain string, or *shell syntax*: <br/>`RUN apt-get install figlet` * JSON list, or *exec syntax*: <br/>`RUN ["apt-get", "install", "figlet"]` We are going to change our Dockerfile to see how it affects the resulting image. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Using exec syntax in our Dockerfile Let's change our Dockerfile as follows! ```dockerfile FROM ubuntu RUN apt-get update RUN ["apt-get", "install", "figlet"] ``` Then build the new Dockerfile. ```bash $ docker build -t figlet . ``` .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## History with exec syntax Compare the new history: ```bash $ docker history figlet IMAGE CREATED CREATED BY SIZE 27954bb5faaf 10 seconds ago apt-get install figlet 1.627 MB 7257c37726a1 About an hour ago /bin/sh -c apt-get update 21.58 MB 07c86167cdc4 4 days ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) CMD ["/bin 0 B <missing> 4 days ago /bin/sh -c sed -i 's/^#\s*\( 1.895 kB <missing> 4 days ago /bin/sh -c echo '#!/bin/sh' 194.5 kB <missing> 4 days ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) ADD file:b 187.8 MB ``` * Exec syntax specifies an *exact* command to execute. * Shell syntax specifies a command to be wrapped within `/bin/sh -c "..."`. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## When to use exec syntax and shell syntax * shell syntax: * is easier to write * interpolates environment variables and other shell expressions * creates an extra process (`/bin/sh -c ...`) to parse the string * requires `/bin/sh` to exist in the container * exec syntax: * is harder to write (and read!) * passes all arguments without extra processing * doesn't create an extra process * doesn't require `/bin/sh` to exist in the container .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Pro-tip: the `exec` shell built-in POSIX shells have a built-in command named `exec`. `exec` should be followed by a program and its arguments. From a user perspective: - it looks like the shell exits right away after the command execution, - in fact, the shell exits just *before* command execution; - or rather, the shell gets *replaced* by the command. .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- ## Example using `exec` ```dockerfile CMD exec figlet -f script hello ``` In this example, `sh -c` will still be used, but `figlet` will be PID 1 in the container. The shell gets replaced by `figlet` when `figlet` starts execution. This allows to run processes as PID 1 without using JSON. ??? :EN:- Towards automated, reproducible builds :EN:- Writing our first Dockerfile :FR:- Rendre le processus automatique et reproductible :FR:- Écrire son premier Dockerfile .debug[[containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Building_Images_With_Dockerfiles.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-cmd-and-entrypoint class: title `CMD` and `ENTRYPOINT` .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-building-docker-images-with-a-dockerfile) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-exercise--writing-dockerfiles) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- class: title # `CMD` and `ENTRYPOINT`  .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Objectives In this lesson, we will learn about two important Dockerfile commands: `CMD` and `ENTRYPOINT`. These commands allow us to set the default command to run in a container. .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Defining a default command When people run our container, we want to greet them with a nice hello message, and using a custom font. For that, we will execute: ```bash figlet -f script hello ``` * `-f script` tells figlet to use a fancy font. * `hello` is the message that we want it to display. .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Adding `CMD` to our Dockerfile Our new Dockerfile will look like this: ```dockerfile FROM ubuntu RUN apt-get update RUN ["apt-get", "install", "figlet"] CMD figlet -f script hello ``` * `CMD` defines a default command to run when none is given. * It can appear at any point in the file. * Each `CMD` will replace and override the previous one. * As a result, while you can have multiple `CMD` lines, it is useless. .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Build and test our image Let's build it: ```bash $ docker build -t figlet . ... Successfully built 042dff3b4a8d Successfully tagged figlet:latest ``` And run it: ```bash $ docker run figlet _ _ _ | | | | | | | | _ | | | | __ |/ \ |/ |/ |/ / \_ | |_/|__/|__/|__/\__/ ``` .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Overriding `CMD` If we want to get a shell into our container (instead of running `figlet`), we just have to specify a different program to run: ```bash $ docker run -it figlet bash root@7ac86a641116:/# ``` * We specified `bash`. * It replaced the value of `CMD`. .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Using `ENTRYPOINT` We want to be able to specify a different message on the command line, while retaining `figlet` and some default parameters. In other words, we would like to be able to do this: ```bash $ docker run figlet salut _ | | , __, | | _|_ / \_/ | |/ | | | \/ \_/|_/|__/ \_/|_/|_/ ``` We will use the `ENTRYPOINT` verb in Dockerfile. .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Adding `ENTRYPOINT` to our Dockerfile Our new Dockerfile will look like this: ```dockerfile FROM ubuntu RUN apt-get update RUN ["apt-get", "install", "figlet"] ENTRYPOINT ["figlet", "-f", "script"] ``` * `ENTRYPOINT` defines a base command (and its parameters) for the container. * The command line arguments are appended to those parameters. * Like `CMD`, `ENTRYPOINT` can appear anywhere, and replaces the previous value. Why did we use JSON syntax for our `ENTRYPOINT`? .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Implications of JSON vs string syntax * When CMD or ENTRYPOINT use string syntax, they get wrapped in `sh -c`. * To avoid this wrapping, we can use JSON syntax. What if we used `ENTRYPOINT` with string syntax? ```bash $ docker run figlet salut ``` This would run the following command in the `figlet` image: ```bash sh -c "figlet -f script" salut ``` .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Build and test our image Let's build it: ```bash $ docker build -t figlet . ... Successfully built 36f588918d73 Successfully tagged figlet:latest ``` And run it: ```bash $ docker run figlet salut _ | | , __, | | _|_ / \_/ | |/ | | | \/ \_/|_/|__/ \_/|_/|_/ ``` .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Using `CMD` and `ENTRYPOINT` together What if we want to define a default message for our container? Then we will use `ENTRYPOINT` and `CMD` together. * `ENTRYPOINT` will define the base command for our container. * `CMD` will define the default parameter(s) for this command. * They *both* have to use JSON syntax. .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## `CMD` and `ENTRYPOINT` together Our new Dockerfile will look like this: ```dockerfile FROM ubuntu RUN apt-get update RUN ["apt-get", "install", "figlet"] ENTRYPOINT ["figlet", "-f", "script"] CMD ["hello world"] ``` * `ENTRYPOINT` defines a base command (and its parameters) for the container. * If we don't specify extra command-line arguments when starting the container, the value of `CMD` is appended. * Otherwise, our extra command-line arguments are used instead of `CMD`. .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Build and test our image Let's build it: ```bash $ docker build -t myfiglet . ... Successfully built 6e0b6a048a07 Successfully tagged myfiglet:latest ``` Run it without parameters: ```bash $ docker run myfiglet _ _ _ _ | | | | | | | | | | | _ | | | | __ __ ,_ | | __| |/ \ |/ |/ |/ / \_ | | |_/ \_/ | |/ / | | |_/|__/|__/|__/\__/ \/ \/ \__/ |_/|__/\_/|_/ ``` .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Overriding the image default parameters Now let's pass extra arguments to the image. ```bash $ docker run myfiglet hola mundo _ _ | | | | | | | __ | | __, _ _ _ _ _ __| __ |/ \ / \_|/ / | / |/ |/ | | | / |/ | / | / \_ | |_/\__/ |__/\_/|_/ | | |_/ \_/|_/ | |_/\_/|_/\__/ ``` We overrode `CMD` but still used `ENTRYPOINT`. .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## Overriding `ENTRYPOINT` What if we want to run a shell in our container? We cannot just do `docker run myfiglet bash` because that would just tell figlet to display the word "bash." We use the `--entrypoint` parameter: ```bash $ docker run -it --entrypoint bash myfiglet root@6027e44e2955:/# ``` .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## `CMD` and `ENTRYPOINT` recap - `docker run myimage` executes `ENTRYPOINT` + `CMD` - `docker run myimage args` executes `ENTRYPOINT` + `args` (overriding `CMD`) - `docker run --entrypoint prog myimage` executes `prog` (overriding both) .small[ | Command | `ENTRYPOINT` | `CMD` | Result |---------------------------------|--------------------|---------|------- | `docker run figlet` | none | none | Use values from base image (`bash`) | `docker run figlet hola` | none | none | Error (executable `hola` not found) | `docker run figlet` | `figlet -f script` | none | `figlet -f script` | `docker run figlet hola` | `figlet -f script` | none | `figlet -f script hola` | `docker run figlet` | none | `figlet -f script` | `figlet -f script` | `docker run figlet hola` | none | `figlet -f script` | Error (executable `hola` not found) | `docker run figlet` | `figlet -f script` | `hello` | `figlet -f script hello` | `docker run figlet hola` | `figlet -f script` | `hello` | `figlet -f script hola` ] .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- ## When to use `ENTRYPOINT` vs `CMD` `ENTRYPOINT` is great for "containerized binaries". Example: `docker run consul --help` (Pretend that the `docker run` part isn't there!) `CMD` is great for images with multiple binaries. Example: `docker run busybox ifconfig` (It makes sense to indicate *which* program we want to run!) ??? :EN:- CMD and ENTRYPOINT :FR:- CMD et ENTRYPOINT .debug[[containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Cmd_And_Entrypoint.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-exercise--writing-dockerfiles class: title Exercise — writing Dockerfiles .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-cmd-and-entrypoint) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-4) | [Next part](#toc-container-networking-basics) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Exercise — writing Dockerfiles 1. Check out the code repository: ```bash git clone https://git.verleun.org/training/docker-build-exercise.git ``` 2. Add a `Dockerfile` that will build the image: * Use `python:3.9.9-slim-bullseye` as the base image (`FROM` line) * Expose port 8000 (`EXPOSE`) * Installs files in '/usr/local/app' (`WORKDIR` ) * Execute the command `uvicorn app:api --host 0.0.0.0 --port 8000` 3. Build the image with `docker build -t exercise:1 .` 4. Run the image: `docker run -d -p 8123:8000 exercise:1` .debug[[custom/Exercise_Dockerfile.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/custom/Exercise_Dockerfile.md)] --- ## Again, with docker-compose (optional) Create a `docker-compose.yml` with the following content: ```yaml version: "3" services: app: build: . ports: - 8123:8000 ``` Start the container: `docker-compose up -d` .debug[[custom/Exercise_Dockerfile.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/custom/Exercise_Dockerfile.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-container-networking-basics class: title Container networking basics .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-exercise--writing-dockerfiles) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-5) | [Next part](#toc-application-configuration) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- class: title # Container networking basics  .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Objectives We will now run network services (accepting requests) in containers. At the end of this section, you will be able to: * Run a network service in a container. * Connect to that network service. * Find a container's IP address. .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Running a very simple service - We need something small, simple, easy to configure (or, even better, that doesn't require any configuration at all) - Let's use the official NGINX image (named `nginx`) - It runs a static web server listening on port 80 - It serves a default "Welcome to nginx!" page .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Running an NGINX server ```bash $ docker run -d -P nginx 66b1ce719198711292c8f34f84a7b68c3876cf9f67015e752b94e189d35a204e ``` - Docker will automatically pull the `nginx` image from the Docker Hub - `-d` / `--detach` tells Docker to run it in the background - `P` / `--publish-all` tells Docker to publish all ports (publish = make them reachable from other computers) - ...OK, how do we connect to our web server now? .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Finding our web server port - First, we need to find the *port number* used by Docker (the NGINX container listens on port 80, but this port will be *mapped*) - We can use `docker ps`: ```bash $ docker ps CONTAINER ID IMAGE ... PORTS ... e40ffb406c9e nginx ... 0.0.0.0:`12345`->80/tcp ... ``` - This means: *port 12345 on the Docker host is mapped to port 80 in the container* - Now we need to connect to the Docker host! .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Finding the address of the Docker host - When running Docker on your Linux workstation: *use `localhost`, or any IP address of your machine* - When running Docker on a remote Linux server: *use any IP address of the remote machine* - When running Docker Desktop on Mac or Windows: *use `localhost`* - In other scenarios (`docker-machine`, local VM...): *use the IP address of the Docker VM* .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Connecting to our web server (GUI) Point your browser to the IP address of your Docker host, on the port shown by `docker ps` for container port 80.  .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Connecting to our web server (CLI) You can also use `curl` directly from the Docker host. Make sure to use the right port number if it is different from the example below: ```bash $ curl localhost:12345 <!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title>Welcome to nginx!</title> ... ``` .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## How does Docker know which port to map? * There is metadata in the image telling "this image has something on port 80". * We can see that metadata with `docker inspect`: ```bash $ docker inspect --format '{{.Config.ExposedPorts}}' nginx map[80/tcp:{}] ``` * This metadata was set in the Dockerfile, with the `EXPOSE` keyword. * We can see that with `docker history`: ```bash $ docker history nginx IMAGE CREATED CREATED BY 7f70b30f2cc6 11 days ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) CMD ["nginx" "-g" "… <missing> 11 days ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) STOPSIGNAL [SIGTERM] <missing> 11 days ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) EXPOSE 80/tcp ``` .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Why can't we just connect to port 80? - Our Docker host has only one port 80 - Therefore, we can only have one container at a time on port 80 - Therefore, if multiple containers want port 80, only one can get it - By default, containers *do not* get "their" port number, but a random one (not "random" as "crypto random", but as "it depends on various factors") - We'll see later how to force a port number (including port 80!) .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Using multiple IP addresses *Hey, my network-fu is strong, and I have questions...* - Can I publish one container on 127.0.0.2:80, and another on 127.0.0.3:80? - My machine has multiple (public) IP addresses, let's say A.A.A.A and B.B.B.B. <br/> Can I have one container on A.A.A.A:80 and another on B.B.B.B:80? - I have a whole IPV4 subnet, can I allocate it to my containers? - What about IPV6? You can do all these things when running Docker directly on Linux. (On other platforms, *generally not*, but there are some exceptions.) .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Finding the web server port in a script Parsing the output of `docker ps` would be painful. There is a command to help us: ```bash $ docker port <containerID> 80 0.0.0.0:12345 ``` .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Manual allocation of port numbers If you want to set port numbers yourself, no problem: ```bash $ docker run -d -p 80:80 nginx $ docker run -d -p 8000:80 nginx $ docker run -d -p 8080:80 -p 8888:80 nginx ``` * We are running three NGINX web servers. * The first one is exposed on port 80. * The second one is exposed on port 8000. * The third one is exposed on ports 8080 and 8888. Note: the convention is `port-on-host:port-on-container`. .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Plumbing containers into your infrastructure There are many ways to integrate containers in your network. * Start the container, letting Docker allocate a public port for it. <br/>Then retrieve that port number and feed it to your configuration. * Pick a fixed port number in advance, when you generate your configuration. <br/>Then start your container by setting the port numbers manually. * Use an orchestrator like Kubernetes or Swarm. <br/>The orchestrator will provide its own networking facilities. Orchestrators typically provide mechanisms to enable direct container-to-container communication across hosts, and publishing/load balancing for inbound traffic. .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Finding the container's IP address We can use the `docker inspect` command to find the IP address of the container. ```bash $ docker inspect --format '{{ .NetworkSettings.IPAddress }}' <yourContainerID> 172.17.0.3 ``` * `docker inspect` is an advanced command, that can retrieve a ton of information about our containers. * Here, we provide it with a format string to extract exactly the private IP address of the container. .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Pinging our container Let's try to ping our container *from another container.* ```bash docker run alpine ping `<ipaddress>` PING 172.17.0.X (172.17.0.X): 56 data bytes 64 bytes from 172.17.0.X: seq=0 ttl=64 time=0.106 ms 64 bytes from 172.17.0.X: seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.250 ms 64 bytes from 172.17.0.X: seq=2 ttl=64 time=0.188 ms ``` When running on Linux, we can even ping that IP address directly! (And connect to a container's ports even if they aren't published.) .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## How often do we use `-p` and `-P` ? - When running a stack of containers, we will often use Compose - Compose will take care of exposing containers (through a `ports:` section in the `docker-compose.yml` file) - It is, however, fairly common to use `docker run -P` for a quick test - Or `docker run -p ...` when an image doesn't `EXPOSE` a port correctly .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- ## Section summary We've learned how to: * Expose a network port. * Connect to an application running in a container. * Find a container's IP address. ??? :EN:- Exposing single containers :FR:- Exposer un conteneur isolé .debug[[containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Container_Networking_Basics.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-application-configuration class: title Application Configuration .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-container-networking-basics) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-6) | [Next part](#toc-logging) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Application Configuration There are many ways to provide configuration to containerized applications. There is no "best way" — it depends on factors like: * configuration size, * mandatory and optional parameters, * scope of configuration (per container, per app, per customer, per site, etc), * frequency of changes in the configuration. .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Command-line parameters ```bash docker run jpetazzo/hamba 80 www1:80 www2:80 ``` * Configuration is provided through command-line parameters. * In the above example, the `ENTRYPOINT` is a script that will: - parse the parameters, - generate a configuration file, - start the actual service. .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Command-line parameters pros and cons * Appropriate for mandatory parameters (without which the service cannot start). * Convenient for "toolbelt" services instantiated many times. (Because there is no extra step: just run it!) * Not great for dynamic configurations or bigger configurations. (These things are still possible, but more cumbersome.) .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Environment variables ```bash docker run -e ELASTICSEARCH_URL=http://es42:9201/ kibana ``` * Configuration is provided through environment variables. * The environment variable can be used straight by the program, <br/>or by a script generating a configuration file. .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Environment variables pros and cons * Appropriate for optional parameters (since the image can provide default values). * Also convenient for services instantiated many times. (It's as easy as command-line parameters.) * Great for services with lots of parameters, but you only want to specify a few. (And use default values for everything else.) * Ability to introspect possible parameters and their default values. * Not great for dynamic configurations. .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Baked-in configuration ``` FROM prometheus COPY prometheus.conf /etc ``` * The configuration is added to the image. * The image may have a default configuration; the new configuration can: - replace the default configuration, - extend it (if the code can read multiple configuration files). .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Baked-in configuration pros and cons * Allows arbitrary customization and complex configuration files. * Requires writing a configuration file. (Obviously!) * Requires building an image to start the service. * Requires rebuilding the image to reconfigure the service. * Requires rebuilding the image to upgrade the service. * Configured images can be stored in registries. (Which is great, but requires a registry.) .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Configuration volume ```bash docker run -v appconfig:/etc/appconfig myapp ``` * The configuration is stored in a volume. * The volume is attached to the container. * The image may have a default configuration. (But this results in a less "obvious" setup, that needs more documentation.) .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Configuration volume pros and cons * Allows arbitrary customization and complex configuration files. * Requires creating a volume for each different configuration. * Services with identical configurations can use the same volume. * Doesn't require building / rebuilding an image when upgrading / reconfiguring. * Configuration can be generated or edited through another container. .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Dynamic configuration volume * This is a powerful pattern for dynamic, complex configurations. * The configuration is stored in a volume. * The configuration is generated / updated by a special container. * The application container detects when the configuration is changed. (And automatically reloads the configuration when necessary.) * The configuration can be shared between multiple services if needed. .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Dynamic configuration volume example In a first terminal, start a load balancer with an initial configuration: ```bash $ docker run --name loadbalancer jpetazzo/hamba \ 80 goo.gl:80 ``` In another terminal, reconfigure that load balancer: ```bash $ docker run --rm --volumes-from loadbalancer jpetazzo/hamba reconfigure \ 80 google.com:80 ``` The configuration could also be updated through e.g. a REST API. (The REST API being itself served from another container.) .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- ## Keeping secrets .warning[Ideally, you should not put secrets (passwords, tokens...) in:] * command-line or environment variables (anyone with Docker API access can get them), * images, especially stored in a registry. Secrets management is better handled with an orchestrator (like Swarm or Kubernetes). Orchestrators will allow to pass secrets in a "one-way" manner. Managing secrets securely without an orchestrator can be contrived. E.g.: - read the secret on stdin when the service starts, - pass the secret using an API endpoint. .debug[[containers/Application_Configuration.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Application_Configuration.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-logging class: title Logging .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-application-configuration) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-6) | [Next part](#toc-container-super-structure) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Logging In this chapter, we will explain the different ways to send logs from containers. We will then show one particular method in action, using ELK and Docker's logging drivers. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## There are many ways to send logs - The simplest method is to write on the standard output and error. - Applications can write their logs to local files. (The files are usually periodically rotated and compressed.) - It is also very common (on UNIX systems) to use syslog. (The logs are collected by syslogd or an equivalent like journald.) - In large applications with many components, it is common to use a logging service. (The code uses a library to send messages to the logging service.) *All these methods are available with containers.* .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Writing on stdout/stderr - The standard output and error of containers is managed by the container engine. - This means that each line written by the container is received by the engine. - The engine can then do "whatever" with these log lines. - With Docker, the default configuration is to write the logs to local files. - The files can then be queried with e.g. `docker logs` (and the equivalent API request). - This can be customized, as we will see later. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Writing to local files - If we write to files, it is possible to access them but cumbersome. (We have to use `docker exec` or `docker cp`.) - Furthermore, if the container is stopped, we cannot use `docker exec`. - If the container is deleted, the logs disappear. - What should we do for programs who can only log to local files? -- - There are multiple solutions. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Using a volume or bind mount - Instead of writing logs to a normal directory, we can place them on a volume. - The volume can be accessed by other containers. - We can run a program like `filebeat` in another container accessing the same volume. (`filebeat` reads local log files continuously, like `tail -f`, and sends them to a centralized system like ElasticSearch.) - We can also use a bind mount, e.g. `-v /var/log/containers/www:/var/log/tomcat`. - The container will write log files to a directory mapped to a host directory. - The log files will appear on the host and be consumable directly from the host. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Using logging services - We can use logging frameworks (like log4j or the Python `logging` package). - These frameworks require some code and/or configuration in our application code. - These mechanisms can be used identically inside or outside of containers. - Sometimes, we can leverage containerized networking to simplify their setup. - For instance, our code can send log messages to a server named `log`. - The name `log` will resolve to different addresses in development, production, etc. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Using syslog - What if our code (or the program we are running in containers) uses syslog? - One possibility is to run a syslog daemon in the container. - Then that daemon can be setup to write to local files or forward to the network. - Under the hood, syslog clients connect to a local UNIX socket, `/dev/log`. - We can expose a syslog socket to the container (by using a volume or bind-mount). - Then just create a symlink from `/dev/log` to the syslog socket. - Voilà! .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Using logging drivers - If we log to stdout and stderr, the container engine receives the log messages. - The Docker Engine has a modular logging system with many plugins, including: - json-file (the default one) - syslog - journald - gelf - fluentd - splunk - etc. - Each plugin can process and forward the logs to another process or system. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## A word of warning about `json-file` - By default, log file size is unlimited. - This means that a very verbose container *will* use up all your disk space. (Or a less verbose container, but running for a very long time.) - Log rotation can be enabled by setting a `max-size` option. - Older log files can be removed by setting a `max-file` option. - Just like other logging options, these can be set per container, or globally. Example: ```bash $ docker run --log-opt max-size=10m --log-opt max-file=3 elasticsearch ``` .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Demo: sending logs to ELK - We are going to deploy an ELK stack. - It will accept logs over a GELF socket. - We will run a few containers with the `gelf` logging driver. - We will then see our logs in Kibana, the web interface provided by ELK. *Important foreword: this is not an "official" or "recommended" setup; it is just an example. We used ELK in this demo because it's a popular setup and we keep being asked about it; but you will have equal success with Fluent or other logging stacks!* .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## What's in an ELK stack? - ELK is three components: - ElasticSearch (to store and index log entries) - Logstash (to receive log entries from various sources, process them, and forward them to various destinations) - Kibana (to view/search log entries with a nice UI) - The only component that we will configure is Logstash - We will accept log entries using the GELF protocol - Log entries will be stored in ElasticSearch, <br/>and displayed on Logstash's stdout for debugging .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Running ELK - We are going to use a Compose file describing the ELK stack. - The Compose file is in the container.training repository on GitHub. ```bash $ git clone https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training $ cd container.training $ cd elk $ docker-compose up ``` - Let's have a look at the Compose file while it's deploying. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Our basic ELK deployment - We are using images from the Docker Hub: `elasticsearch`, `logstash`, `kibana`. - We don't need to change the configuration of ElasticSearch. - We need to tell Kibana the address of ElasticSearch: - it is set with the `ELASTICSEARCH_URL` environment variable, - by default it is `localhost:9200`, we change it to `elasticsearch:9200`. - We need to configure Logstash: - we pass the entire configuration file through command-line arguments, - this is a hack so that we don't have to create an image just for the config. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Sending logs to ELK - The ELK stack accepts log messages through a GELF socket. - The GELF socket listens on UDP port 12201. - To send a message, we need to change the logging driver used by Docker. - This can be done globally (by reconfiguring the Engine) or on a per-container basis. - Let's override the logging driver for a single container: ```bash $ docker run --log-driver=gelf --log-opt=gelf-address=udp://localhost:12201 \ alpine echo hello world ``` .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Viewing the logs in ELK - Connect to the Kibana interface. - It is exposed on port 5601. - Browse http://X.X.X.X:5601. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## "Configuring" Kibana - Kibana should offer you to "Configure an index pattern": <br/>in the "Time-field name" drop down, select "@timestamp", and hit the "Create" button. - Then: - click "Discover" (in the top-left corner), - click "Last 15 minutes" (in the top-right corner), - click "Last 1 hour" (in the list in the middle), - click "Auto-refresh" (top-right corner), - click "5 seconds" (top-left of the list). - You should see a series of green bars (with one new green bar every minute). - Our 'hello world' message should be visible there. .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- ## Important afterword **This is not a "production-grade" setup.** It is just an educational example. Since we have only one node , we did set up a single ElasticSearch instance and a single Logstash instance. In a production setup, you need an ElasticSearch cluster (both for capacity and availability reasons). You also need multiple Logstash instances. And if you want to withstand bursts of logs, you need some kind of message queue: Redis if you're cheap, Kafka if you want to make sure that you don't drop messages on the floor. Good luck. If you want to learn more about the GELF driver, have a look at [this blog post]( https://jpetazzo.github.io/2017/01/20/docker-logging-gelf/). .debug[[containers/Logging.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Logging.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-container-super-structure class: title Container Super-structure .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-logging) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-6) | [Next part](#toc-links-and-resources) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Container Super-structure - Multiple orchestration platforms support some kind of container super-structure. (i.e., a construct or abstraction bigger than a single container.) - For instance, on Kubernetes, this super-structure is called a *pod*. - A pod is a group of containers (it could be a single container, too). - These containers run together, on the same host. (A pod cannot straddle multiple hosts.) - All the containers in a pod have the same IP address. - How does that map to the Docker world? .debug[[containers/Pods_Anatomy.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Pods_Anatomy.md)] --- class: pic ## Anatomy of a Pod  .debug[[containers/Pods_Anatomy.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Pods_Anatomy.md)] --- ## Pods in Docker - The containers inside a pod share the same network namespace. (Just like when using `docker run --net=container:<container_id>` with the CLI.) - As a result, they can communicate together over `localhost`. - In addition to "our" containers, the pod has a special container, the *sandbox*. - That container uses a special image: `k8s.gcr.io/pause`. (This is visible when listing containers running on a Kubernetes node.) - Containers within a pod have independent filesystems. - They can share directories by using a mechanism called *volumes.* (Which is similar to the concept of volumes in Docker.) .debug[[containers/Pods_Anatomy.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/Pods_Anatomy.md)] --- class: title, self-paced Thank you! .debug[[shared/thankyou.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/thankyou.md)] --- class: title, in-person That's all, folks! <br/> Questions?  .debug[[shared/thankyou.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/shared/thankyou.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-links-and-resources class: title Links and resources .nav[ [Previous part](#toc-container-super-structure) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-part-6) | [Next part](#toc-) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Links and resources - [Docker Community Slack](https://community.docker.com/registrations/groups/4316) - [Docker Community Forums](https://forums.docker.com/) - [Docker Hub](https://hub.docker.com) - [Docker Blog](https://blog.docker.com/) - [Docker documentation](https://docs.docker.com/) - [Docker on StackOverflow](https://stackoverflow.com/questions/tagged/docker) - [Docker on Twitter](https://twitter.com/docker) - [Play With Docker Hands-On Labs](https://training.play-with-docker.com/) .footnote[These slides (and future updates) are on → https://container.training/] .debug[[containers/links.md](https://git.verleun.org/training/containers.git/tree/main/slides/containers/links.md)]